US withdrawal from the WHO shines spotlight on need for reform

Amidst the whirlwind of executive orders issued by incoming US President Donald Trump last week was the news that the US intends to withdraw from the World Health Organisation (WHO).

The move has been met with widespread condemnation from experts citing concerns about the effects of budget cuts to the WHO, and the isolation of public health institutions in America.

At the same time, the news has shone the spotlight on problems within the WHO that have until now been largely ignored, with the potential to trigger reform that could benefit the global health network.

At roughly $600 million per year in contributions, the US provides about one fifth of the WHO’s $3.4 billion budget (USD), leaving a considerable shortfall that needs to be met either by other nation states or private donors in the absence of US membership.

In a statement on X, the WHO urged the US to reconsider its withdrawal, highlighting the nation’s role as a founding member of the organisation in 1948, and decades of achievements through their global health partnership.

“For over seven decades, WHO and the USA have saved countless lives and protected Americans and all people from health threats. Together, we ended smallpox, and together we have brought polio to the brink of eradication,” said the WHO.

This is President Trump’s second attempt at withdrawing from the WHO, after his first executive order signalling intention to withdraw in 2020 was revoked by the Biden administration in 2021.

The executive order, issued on 20 January, sets the clock on a 12-month notice period for the US to leave the United Nations health agency.1 During this time, the US will cease negotiations on the WHO’s major pandemic reforms: a binding treaty, and amendments to the International Health Regulations.

The US Government will now work to “identify credible and transparent United States and international partners to assume necessary activities previously undertaken by the WHO,” according to the order.

Much has been written in the past week about the potential impacts of this decision on the health of Americans, and the world:

The withdrawal “would undermine the nation’s standing as a global health leader and make it harder to fight the next pandemic,” wrote the New York Times.

“The loss could hinder the WHO’s ability to swiftly and effectively respond to infectious disease outbreaks and other emergencies around the world, among others,” wrote Politico, along with concerns that the US will lose access to the global network that sets the flu vaccine’s composition every year.2

Experts told ABC that, "Trump could be sowing the seeds for the next pandemic,” and, "the irrational withdrawal” will make “the USA vulnerable to decreased human capital and quality of life on all health indicators, lack of guidance on informed health emergencies, depleted health literacy and increase in non-communicable and communicable diseases."

The news has already triggered budget cuts at the WHO, said Bloomberg, reporting a verified internal memo to staff from WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in which he said that the US withdrawal “has made our financial situation more acute,” necessitating “cost reductions and efficiencies.“ Projected cuts include a hiring freeze, curtailment of travel expenditure, and suspension of office refurbishments and expansions.

Another executive order putting a freeze on foreign aid has brought the potential effects of US withdrawal from public health programs into stark relief, affecting the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief program, which supplies most of the treatment for HIV in Africa and developing countries.

The New York Times reported that patients are already being turned away from clinics, medications are being withheld, and US officials have been instructed to stop providing technical assistance to national ministries of health.

However, notably missing from coverage of the US’s WHO withdrawal is robust discussion of the validity (or otherwise) of the Trump administration’s criticisms.

The art of the deal

Trump cited “the organization’s mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic that arose out of Wuhan, China, and other global health crises, its failure to adopt urgently needed reforms, and its inability to demonstrate independence from the inappropriate political influence of WHO member states,” as reasons for the US’s intention to withdraw from the WHO.

Additionally, “the WHO continues to demand unfairly onerous payments from the United States, far out of proportion with other countries’ assessed payments. China, with a population of 1.4 billion, has 300 percent of the population of the United States, yet contributes nearly 90 percent less to the WHO,” said the executive order.

It is true that the US provides far more towards the WHO budget than China's $80 million per annum. While China has the larger population, WHO member state contributions are assessed on the size of the nation’s economy, not the population, a fact which seems to be the basis of Trump’s complaint.

However, the majority of the US’s contributions are voluntary, over and above the required member state ‘assessed contributions.’ While China’s assessed contributions are less than half ($45 million p.a.) than those of the US ($110 million p.a.), the significant difference is in the disparity between voluntary contributions made by the two countries.3

In this respect, it is possible that the withdrawal notice is a play in the hard-nosed art of dealmaking.

“I suspect this is the thinking behind Trump’s executive order - that it is intended as laying down the gambit to make a deal,” public health physician and former WHO medical officer, Dr David Bell told me over email.

While this might involve angling for higher contributions from other countries and lower contributions from the US, Trump’s complaints against the WHO indicate that he may also be pursuing the goal of institutional reform. If a deal cannot be made, then the US will presumably follow through with the threat of leaving the WHO.

Reforming international public health

“I think the administration believes international organizations are useful in health, but the WHO is clearly not fit for purpose,” said Dr Bell, whose extensive work with the REevaluating the Pandemic Preparedness And REsponse agenda (REPPARE) working group, in collaboration with the University of Leeds, has brought the WHO’s pandemic risk assessment and response plans into question.

A trade-off for the US will be loss of influence. “It will be unfortunate to leave the WHO more firmly in the hands of geopolitical rivals and private interest groups,” says Dr Bell, but “the WHO needs a jolt, and if reform cannot happen, the US and many other countries should leave.”

“The best approach is to demand radical reform, and to replace the WHO if reform proves impossible.”

In a recent article titled ‘Global Health Reform Must Go Far Beyond WHO’ for Brownstone Institute, Dr Bell described the “institutional rot” of a “vast and detached bureaucracy,” beholden to private donors who can dictate how their donations are spent, and engaging in luxury belief politics while exacerbating inequalities in developing countries.

The WHO’s mandate is to promote health, which it defines as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. Yet during the pandemic, wrote Dr Bell, the WHO’s promotion of extremist policies,

“…helped force over a hundred million additional people into severe food insecurity and poverty and up to ten million additional girls into child marriage and sexual slavery.

“It helped deprive a generation of the schooling needed to lift themselves out of poverty and grew national debts to leave countries at the mercy of global predators. This was an intentional response to a virus they knew from the beginning was rarely severe beyond sick elderly people.

“The WHO helped orchestrate an unprecedented transfer of wealth from those it was originally tasked to protect to those who now sponsor and direct most of its work. Lacking any contrition, the WHO is now seeking increased public funding through misrepresentation of risk and return on investment to entrench this response.”

Instead of expanding its budget and control with new pandemic reforms, Dr Bell says that the WHO “should be steadily downsizing as national capacity is built, and it should be concentrated on what makes us healthier and longer-lived, not rare outbreaks that are profitable but have very small mortality.”

Here, Dr Bell points out that, given that Covid is almost certainly the result of a lab leak after gain-of-function research, it is irrelevant to the surveillance network being built by the WHO to mitigate pandemic risk.

“We have not had a major outbreak in over 100 years that is in the category of natural outbreaks that the pandemic agenda is designed for,” he said.

This was confirmed with the release this week of a CIA analysis favouring (with low confidence) the lab leak as the origin of Covid. The FBI previously arrived at the same conclusion with moderate confidence.

On this point, Dr Bell said the US withdrawal “raises the importance of getting the truth regarding pandemic risk and funding more widely known.”

US withdrawal opens dialogue

This is a silver lining also noted by the Aligned Council of Australia (ACA), a collective formed in opposition to the WHO’s pandemic treaties, representing over 1.7 million Australians across 39 member organisations.

Like Dr Bell, ACA co-founder and lawyer Katie Ashby-Koppens suspects Trump’s executive order is more likely intended to “negotiate a cheaper deal” than a committed withdrawal, but said that the order has opened the way for conversation about the WHO’s structure and conduct.

“The Trump administration’s WHO withdrawal notice puts a microscope on the organisation, whereas before it’s been like teflon - nothing would stick, and no one in authority would talk about it,” said Ashby-Koppens.

“This order gives credence to concerns that groups like ours have been raising about the WHO for a long time.”

These concerns include conflicts presented by the private-public partnership model, centralisation of decision-making powers, bureaucratic bloat, disconnection from the lived experience of people on the ground who the WHO’s actions affect, and lack of transparency.

Ashby-Koppens acknowledges that a mass exodus from the WHO is unlikely, and that Australia is committed as ever, providing an additional $100 million (AUD) in voluntary funding to the WHO for pandemic preparedness over the next five years over and above its assessed (required) contributions.

A spokesperson for the Department of Health confirmed,

“Australia is committed to supporting the WHO and its unique mandate as the coordinating body on international health work, which helps to keep Australia, our region and the world safe.

“We will continue to work with partners, including the US, to strengthen global health cooperation to prepare for and respond to future health emergencies.”

Accordingly, ACA is focusing on the points it has a chance of scoring.

“I think we need to question the amount of money we’re giving to WHO and where it’s going. $100 million in voluntary contributions is a phenomenal amount in a cost of living crisis,” said Ashby-Koppens.

In 2024, one in eight Australians was living in poverty, more than half of low-income households experienced food insecurity, and 60% of Australians lived paycheck to paycheck.

If upcoming WHO agreements are adopted, public spending on the international public health apparatus will only increase, said Ashby-Koppens.

Negotiations over the international pandemic treaty have stalled, but Health Minister Mark Butler has previously signalled Australia’s strong commitment to seeing the negotiations through and adopting the treaty when finalised.

New International Health Regulation (IHR) amendments have been adopted and will become binding this year, but Australia has until July 2025 to opt out by formally rejecting them.

The IHR amendments could essentially lead to “perpetual pandemics,” said Ashby-Koppens, referring to the extensive surveillance networks that countries will be obligated to implement, whereby everyone, everywhere will be searching for new viruses all the time.

When paired with the planned treaty, the WHO will not only get to define what a pandemic is (as it did with a controversially low bar with Mpox), it will define what treatments and prophylactics are acceptable, it will require member states to legislate to bring in directed health measures - which can include proof of vaccination, mandatory vaccination, medical examinations, contact tracing, and quarantine - and it can require that member states censor information that is deemed to be ‘misinformation.’

The costs are not always direct, either. According to a parliamentary report, the Australian Government granted indemnity to Covid vaccine manufacturers under the guidance of the WHO as a requirement of its participation in the WHO-led COVAX project.

This has left member state governments to foot the bill for vaccine injuries, amounting to nearly $40 million in Australia thus far, and much more if over 2,000 Australians currently suing the government in a Covid vaccine injury class action are successful.

Moreover, nation states participating in COVAX were pressured to fund vaccines for poorer nations, in addition to their regular WHO contributions. This is reportedly the main sticking point for the UK in its rejection of the WHO pandemic treaty in its current form, as it would allegedly force Britain to give away a fifth of its vaccines in a future pandemic.

Last year, a small group of Australian politicians pressed the Prime Minister to reject the reforms on the basis that they posed “a significant threat to Australia’s autonomy and independence on the global stage,” but the resistance has so far been ineffectual.

However, ACA believes there is a real chance of community-driven opposition stopping the treaty and IHR amendments from going through Down Under.

“We encourage everyone who cares about Australia’s health sovereignty to join our campaign to make the rejection of the WHO’s pandemic reforms an election issue for 2025,” said Ashby-Koppens.

What the world needs now

Regardless of the future of the WHO, Dr Bell said he hopes the world can “have a small, focused, and ethical international health agency that addresses needs of countries when requested and focusses on diseases of high burden.”

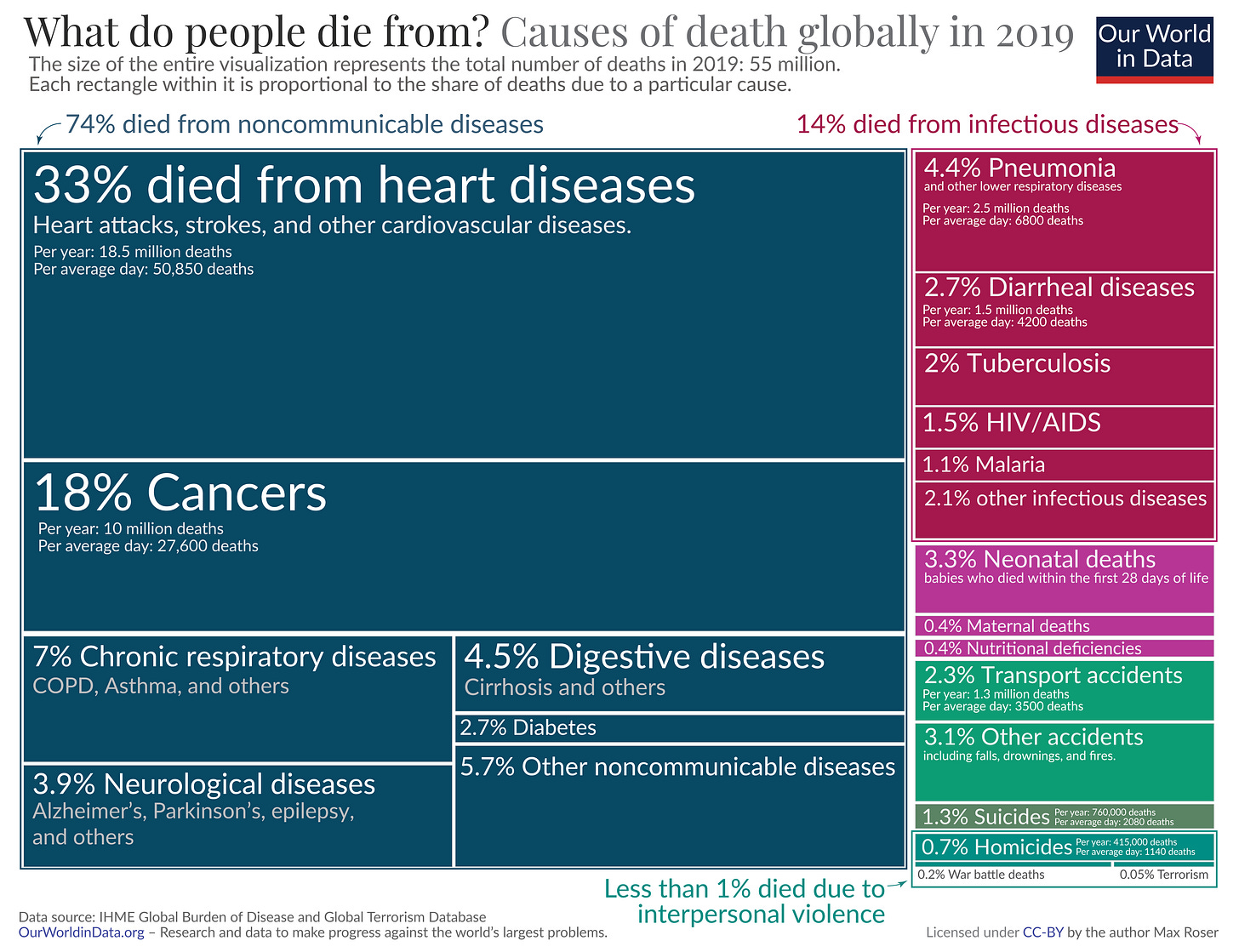

While an estimated seven million people died with Covid during the first five years of the likely man-made pandemic, more than 600,000 people die of malaria and 1.3 million from tuberculosis every year, far eclipsing the cumulative mortality rate from pandemics over a longer time horizon.4

By far the biggest killers are non-communicable diseases like cardiovascular disease and cancers, which are responsible for half of all deaths worldwide.

“Whether the WHO still exists in some form to be part of that depends on the willingness of its staff to do what they are mandated to do, rather than what is good for career-building and personal gain,” he said. “I do believe there are still a lot of decent people there, but it needs radical change.”

If radical change is not implemented, the WHO may find that its support continues to dwindle.

Italy’s right-wing Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini has already proposed a bill to follow the US withdrawal from the WHO. If more countries signal loss of confidence in the WHO, we may see splintering in the way international health is managed, from a centralised format (represented by the WHO) to several agencies preferred by different blocs of nations, or even something more decentralised.

The WHO does important work that saves lives - supporting low-resource countries in dealing with endemic infectious diseases, assisting to reduce exposure to fake pharmaceuticals (one of the largest criminal industries on earth, says Dr Bell), and working to strengthen under-resourced health systems.

The question is whether the WHO is the best agency to do this work, and whether it can stop the rot to do maximum good without causing collateral damage in train.

To support my work, share, subscribe, and/or make a one-off contribution to my Kofi account. Thanks!

Physician researcher Meryl Nass disputes this on the basis that the notice was already given with Trump’s first executive order notifying the WHO of the US’s intention to exit in 2020.

Nass also disputes this point, arguing that flu strain data comes from Australia, which the U.S. will not lose access to.

Voluntary contributions can be unconditional or specified to go towards the projects that the donor wishes. In the U.S.’s case, voluntary contributions are specified, going mainly towards acute health emergencies, improving access to essential health services, and polio eradication.

Not to mention that more than half of the 15 million excess deaths during the first two years of the Covid pandemic were not related to Covid infections, but were more likely downstream effects of the extremist policies endorsed by the WHO and implemented by member states.

My medical diagnosis is that the WHO's condition is terminal and euthanasia would be the kindest treatment.

I cannot see such a level of corruption being amenable to any remedy.

The old WHO used to be good. We still use their standards for assessing clean water for example.

The new WHO, as demonstrated via the Covid years, is an abomination.

A few more countries giving them the flick might make them revert back to the old WHO.