'Spectacular backfire': Australian government's attempt to censor trans post draws heat

A threatening notice issued by the online safety regulator has brought renewed attention to Australia’s heavy-handed approach to censorship and its extreme gender affirming care laws

First it took down tweets on breastfeeding. Now, Australia’s online safety regulator, the eSafety Commissioner, has threatened social media platform X (formerly Twitter) with a hefty fine over a post characterising the trans male identification of a bearded natal female as a psychiatric condition.

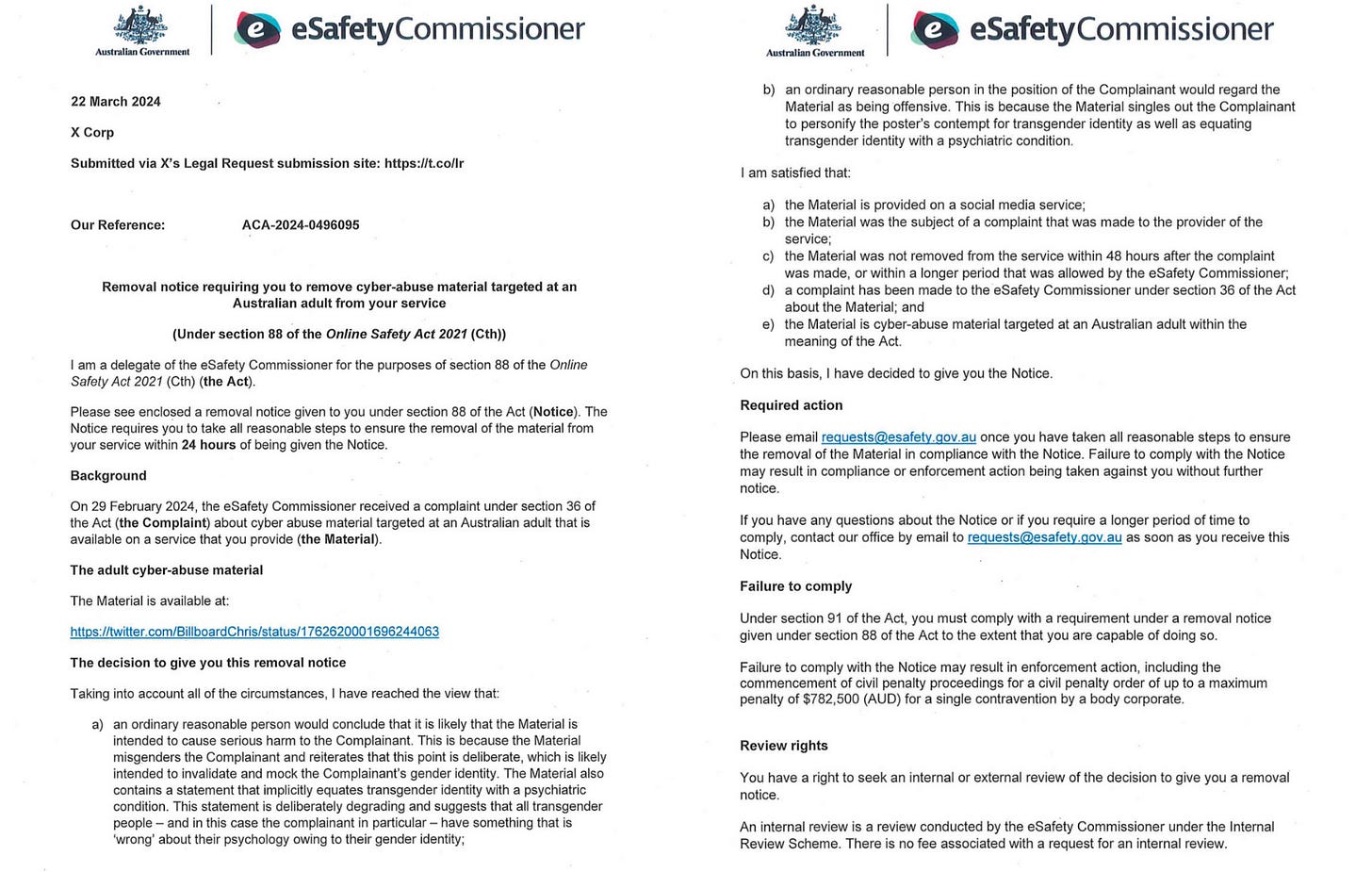

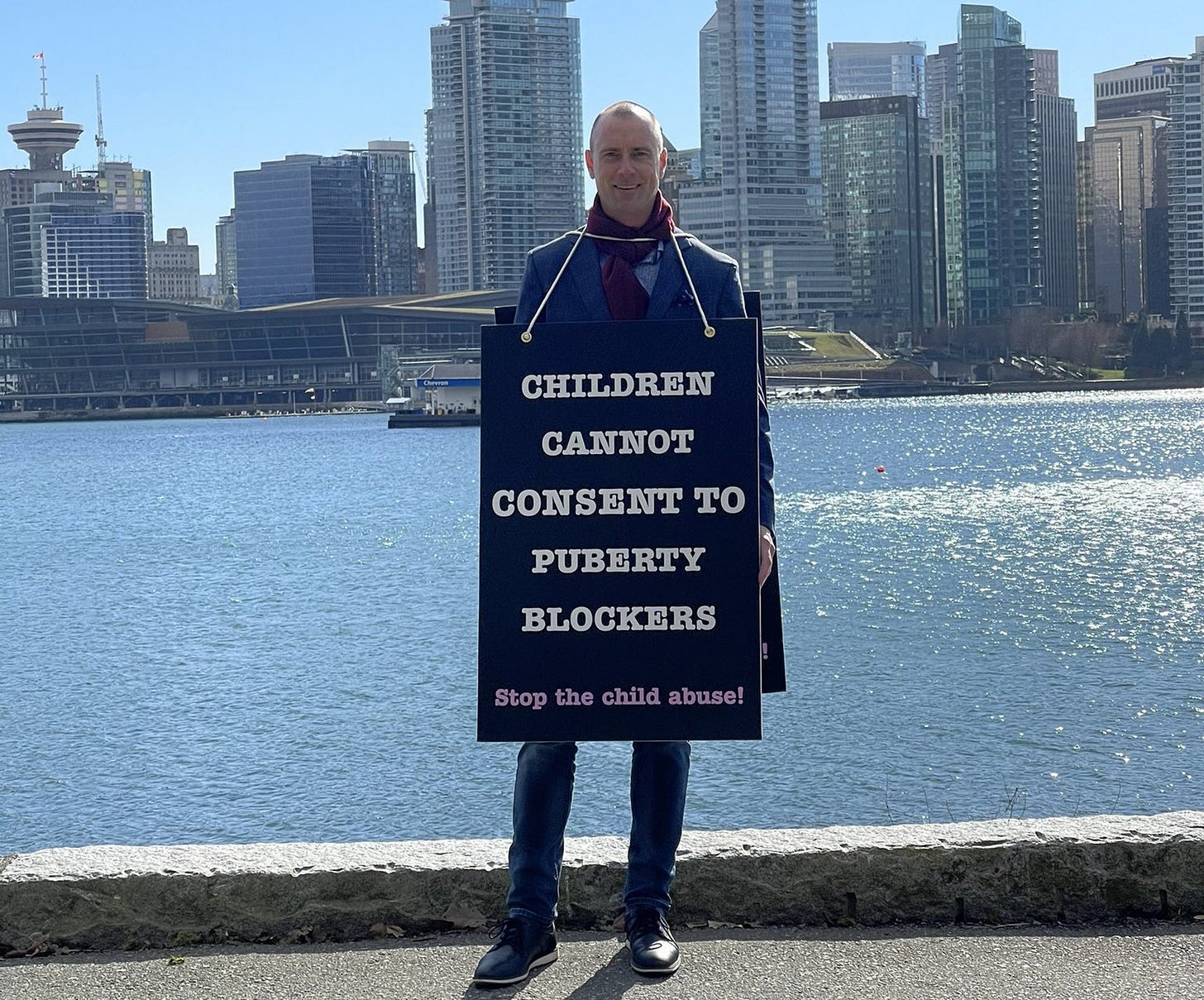

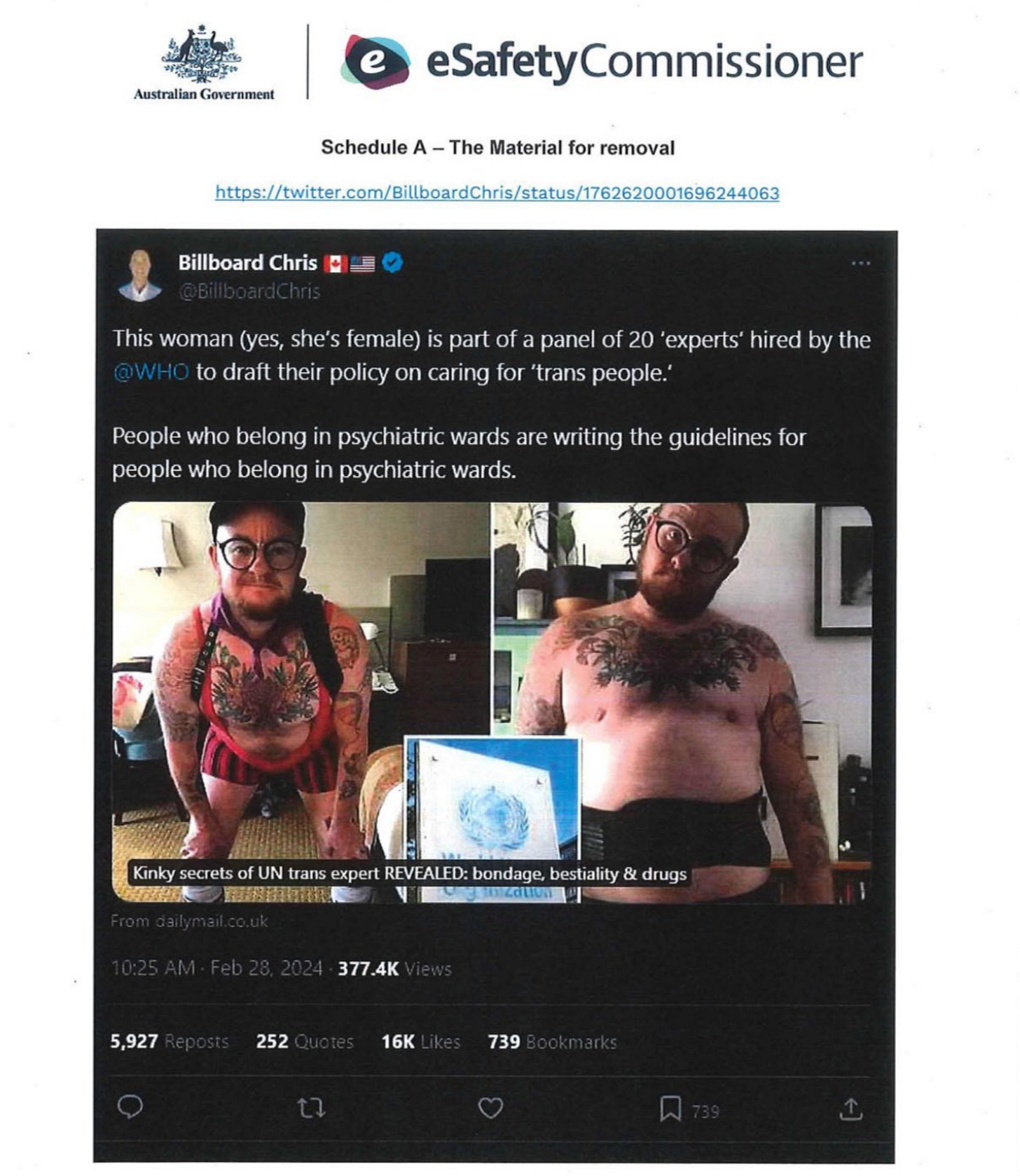

In a notice issued to X on 22 March, eSafety gave the platform 24 hours to take down the post by Canadian activist Chris Elston, whose moniker ‘Billboard Chris’ is a nod to his frequent public demonstrations wearing billboards carrying messages against gender ideology and medicine, especially in relation to children.

The notice threatens civil penalty proceedings and a maximum penalty of AUD $782,500 for failure to comply.

“This woman (yes she’s a female) is part of a panel of 20 ‘experts’ hired by the WHO to draft their policy on caring for ‘trans people.’ People who belong in psychiatric wards are writing the guidelines for people who belong in psychiatric wards,” states Elston’s caption, along with a link to a salacious Daily Mail article about the individual, Teddy Cook.

The offending post is no longer visible to Australian users, but as of last night Australian time (Tuesday morning Canada time), Elston told Dystopian Down Under that the post remained up and was visible to users outside of Australia.

eSafety’s removal notice, which Elston posted publicly after it was forwarded to him by X, states that Elston’s post is cyber-abuse material which “an ordinary reasonable person” would conclude is “intended to cause serious harm to the Complainant.”

eSafety does not actively surveil social media sites, but responds to complaints reported to its online portal. The identity of the Complainant refered to in eSafety’s removal notice is unknown.

I asked eSafety how it determines what an ‘ordinary reasonable person’ would find offensive on subjective and polarising matters such as trans medicine and gender identity. In some parts of the internet, Elson is reviled as an anti-trans hatemonger. In other parts, he is praised for his tireless efforts to prevent child abuse. A spokesperson responded,

“The Online Safety Act defines adult cyber abuse as material targeting a particular Australian adult that is both:

intended to cause serious harm, and

menacing, harassing or offensive in all the circumstances.

“If the material only meets one of the two criteria above (for example, if something is offensive but is not intended to cause serious harm), that will not be considered adult cyber abuse under the Act.

“Under the Act, the term ‘adult cyber abuse’ is reserved for the most severely abusive material intended to cause serious psychological or physical harm. This would include material which sets out realistic threats, places people in real danger, is excessively malicious or is unrelenting.

“eSafety may consider material collectively when assessing its overall seriousness.”

I also asked how eSafety determines the dollar value of fines in proportion to the perceived offense. Some may view a fine of three quarters of a million dollars for a single post to be a disproportionate.

The eSafety spokesperson responded,

“Where a person fails to comply with a removal notice, they can face a civil penalty of up to 500 penalty units. eSafety may also consider several other enforcement options. The monetary value of 1 penalty unit is $313 for individuals.

“The maximum penalty ordered against a corporation (which can include online service providers) can be 5 times more than the maximum penalty ordered against individual.”

This means that an individual can face a penalty of up to AUD $156,500 for a failing to remove a single post, and a corporaton can be penalised $782,500.

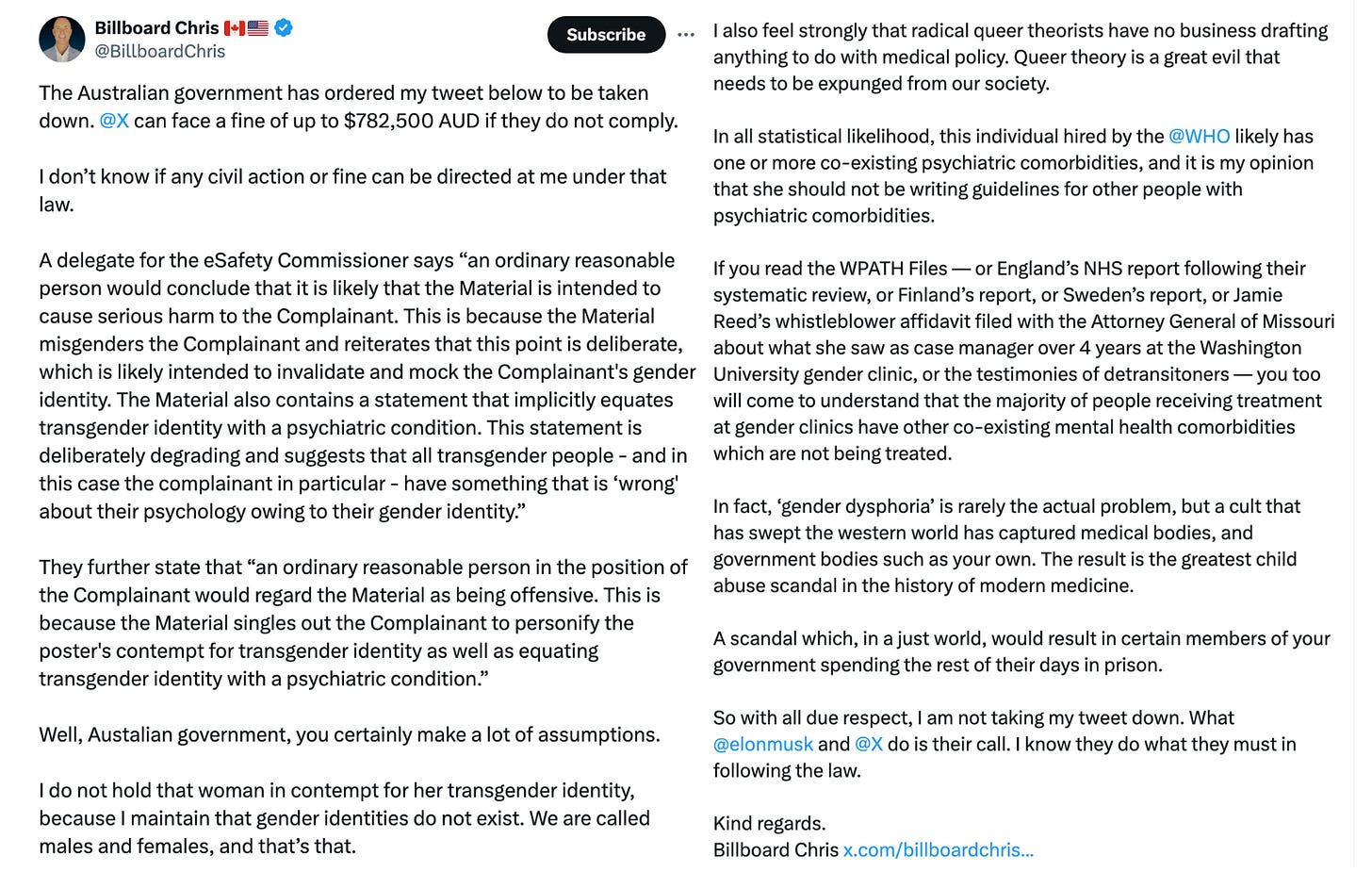

For Elston’s part, he maintains that eSafety’s move to ban his post has “backfired spectacularly,” drawing more attention to his activism against gender ideology and the medicalisation of gender confused children.

Responding to eSafety’s removal notice in a post on X, Elston wrote,

“Well, Austalian government, you certainly make a lot of assumptions. I do not hold that woman in contempt for her transgender identity, because I maintain that gender identities do not exist.”

In the same post, Elston referred to the recently released WPATH Files, a cache of leaked internal communications between members of the World Professional Association of Transgender Health (WPATH).

Compiled and analysed by researcher Mia Hughes for US-based think tank Enivronmental Progress, the WPATH Files reveal questionable standards of care involving “pseudoscientific surgical and hormonal experiments on children, adolescents, and vulnerable adults.”

In the files, medical practioners were observed to have freqently based their gender medicine practice on hunches and anecdotal advice, not science.

Furthermore, the files “provide clear evidence that doctors and therapists are aware they are offering minors life-changing treatments they cannot fully understand,” writes Hughes.

It’s “the greatest child abuse scandal in the history of modern medicine,” says Elston, who is father to two daughters.

The release of the WPATH files times with a shift in sentiment away from unquestioningly promoting gender affirming care, towards a more rational approach that takes into account the need for evidence-based medical decision making, and the long term impacts of gender medicine.

The UK’s famed Tavistock Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) for children and adolescents is set to close at the end of this month, after an independent review of the UK’s gender affirming care services reported that there was an evidence gap and overall lack of consensus and open discussion about the nature of gender dysphoria and appropriate clinical treatments.

This month, the UK’s National Health Service banned puberty suppressing hormones (PSH) in routine treatment of children and young people with gender dysphoria on the basis that “there is not enough evidence to support the safety or clinical effectiveness of PSH to make the treatment routinely available at this time.”

In Australia, a Channel 7 special program hosted by veteran journalist Liam Bartlett and featuring de-transitioners aired on TV late last year and has had over 660,000 views on YouTube, turning the national spotlight onto the dark side of gender affirming care.

In light of these developments, an ‘ordinary reasonable person’ might find Elston’s activism work, and even his acerbic social media posts, to be… reasonable.

Yet Australian lawmakers are forging ahead with the affirmation-only model that WPATH Files and the UK’s policy changes bring into question.

In Victoria, under the Change or Suppression (Conversion) Practices Prohibition Act 2021, it could be a criminal offence to attempt to counsel a gender-questioning child or adolescent in any way that does not outright affirm their professed identity.

A post titled, ‘Not affirming transgender children is family violence in Victoria’, on the Human Rights Law Alliance website notes with concern,

“Victoria now has a new legal basis to compel parents to endorse their children if they pursue a transgender identity. [Parents] will no longer be able to follow their conscience and their instincts as parents – to continue to affirm biological reality and their lived experience of the child that they raised. Anything less than affirmation could have serious consequences.”

A motion brought by Victorian conservative Liberal MP Moira Deeming for an inquiry into gender-affirming care for children was voted down in October last year, with the Labor Party and the Greens voting against the inquiry.

New South Wales passed similar anti-conversion legislation this month, with the State Government noting that the new laws bring NSW into line with other states and territories where conversion practices are outlawed, including in Victoria, Queensland, the Australian Capital Territory, New Zealand and Canada.

As well as focusing the social-media-sphere’s attention on Australia’s gender affirming laws and practices, particularly for children, the Billboard Chris episode has sparked renewed criticism of Australia’s heavy-handed approach to online censorship and the eSafety Commissioner, Julie Inman Grant’s apparently personal vendetta against Elon Musk.

Australia made international headlines last year when a Freedom of Information (FOI) request filed by Liberal Senator Alex Antic revealed that the Department of Home Affairs (DHA) had made over 4,000 requests to digital platforms to take down content related to Covid.

Hot on the heels of this release, an Australian Twitter Files drop filled in some of the detail. Posts flagged by the DHA for takedown included a meme making fun of Victorian Premier Dan Andrews, and a post with just eight likes.

The Department of Health (DOH) also got in on the act. Another FOI request unearthed a trail of co-operative communications between the DOH and social media platforms, with the DOH flagging content for takedown and the platforms obliging. In one communication, the DOH flagged a Facebook group sharing “vaccine reactions that are not substantiated.” Facebook responded that it had taken down the group.

While these instances focused on Covid-related posts, the eSafety Commissioner weighed in on the culture wars. In the same week that the DHA story broke, eSafety hit the headlines for its no-nonsense stance on transgender breastfeeding.

eSafety prevented Australian users from seeing posts by breastfeeding advocate Jasmine Sussex on X, then Twitter, which the regulator deemed to be in violation of Australian law. The posts expressed criticism of an article about a transgender woman attempting to lactate.

Since Elon Musk purchased the Twitter platform in 2022, eSafety has ratcheted up the pressure on X.

Inman Grant, who previously worked at Twitter, has publicly criticised Elon Musk’s ‘new Twitter’ on numerous occasions, noting that X’s trust and safety teams have “seriously diminished” under Musk’s leadership, and accusing Musk of allowing “sewer rats” back onto the platform.

In December last year, eSafety initiated civil penalty proceedings against X in the Federal Court over its alleged failure to comply with a request for information. If found non-compliant, X could be fined up to $780,000 per day, backdated to March 2023, when the determination of non-compliance was made.

eSafety has no further information on the status of the civil penality proceedings at this time.

Inman Grant, who is affiliated with the World Economic Forum (WEF), famously suggested a “recalibration” of human rights in online spaces, including freedom of speech, at a WEF meeting in 2022.

And she may get her way. Australia’s other digital regulator, the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) is poised to target platforms for mis- and disinformation if a bill that is currently under review gets passed later this year.

As the government and mainstream media are exempt from ACMA’s proposed new powers, it will be the speech of everyday users that will be most impacted should the legislation pass. And we can be sure that the definitions of mis- and disinformation will work to the assumption that the government is always right (everything else is misinformation).

Nevertheless, none of this has any bearing on Elston and his billboard. In an email to Dystopian Down Under, Elston said, “No matter what lawmakers do, I will keep taking my message to the streets, out in the real world, until the practice of child transition is ended worldwide.”

To support my work, make a one-off contribution to DDU via my Kofi account and/or subscribe. Thanks!

Two queries from readers that I wish I'd addressed more clearly in the article, and so will pin here instead:

1. Q: Was the censored speech illegal or not?

A: My understanding is that the speech is not illegal per se, but under the Online Safety Act, eSafety can determine it illegal within the context of being displayed on a digital platform. The OSA gives eSafety leeway to decide that certain speech on social media platforms, if the subject of a Complaint, is 'harmful' if an 'ordinary reasonable person' would deem it to be so. This is obviously highly subjective. However, the OSA gives eSafety the power to make subjective calls on this basis and to then declare it illegal for these certain posts which have been deemed 'harmful' to remain visible to Australian users.

2. Q: Is eSafety well-intentioned or are they going after certain users maliciously?

A: My impression, from the communications that I've had with had with various staff at eSafety is that they are well-intentioned and that these instances of culture war censorship occur in the grey area in their broader work of addressing online harm, such as removing child abuse or revenge porn content. My opinion is that eSafety staff are probably unaware of the problems arising from the degree of subjectivity allowed within the application of the OSA, particularly pertaining to charged political and social issues such as trans identity and medicine. I think that eSafety predominantly does great work and protects a lot of vulnerable people from online abuse. I have noted this in previous articles about eSafety and will endeavour to keep mentioning it going forward. That said, I think that eSafety head Julie Inman Grant is a different case. She appears to have a strong dislike of Elon Musk and his approach to speech. The combination of her public comments and eSafety's actions against X lead me to think (just my opinion, I can't prove it) that she probably has somewhat of a vendetta against Musk and the platform, which is influencing her professional conduct.

Thank you for this post Rebekah. These woke, leftist bureaurcrats & politicians who give them power, are way out of step with mainstream, normal people. It is a joke, but not a funny one!