Measles: A Balanced Perspective

An informational resource for people who want just the facts, no agenda

In keeping with international trends, Australian media are reporting a ‘measles outbreak’ due to travellers coming into the country and spreading the disease.

Media reports state that measles was eradicated in Australia in 2014, but now it’s back, at a time when childhood measles vaccination has taken a dip. There has been great emphasis on the highly contagious nature of the disease and its potential life-altering effects, such as encephalitis.

We are told that the only way to protect yourself and everyone around you is to be vaccinated, and to be wary of ‘misinformation’ on social media, such as the idea that the MMR vaccine causes autism or that Vitamin A can cure measles.

On the other hand, in independent media there has been reactionary reporting declaring measles to be non-harmful, warning people off vaccination altogether, and promoting alternative treatments.

What there has been little of is balanced presentation of evidence-based information on measles and its prospective treatments to enable YOU to make informed decisions.

To fill this gap, Inform Me recently ran a webinar on measles, hosted by Rebekah Barnett (chief question-asker) and panellists with a range of views to explore the risks and benefits of the disease itself and the available treatment options. Rather than promoting a singular viewpoint, the conversation sought to open space for a more nuanced understanding of the topic.

Watch the Inform Me webinar here.

Panellists included Dr Joe Kosterich, a GP, speaker, author, and health industry consultant; Professor Ian Brighthope, expert in nutritional, environmental and herbal medicine and founding president of the Australasian College of Nutritional and Environmental Medicine (ACNEM); and Robyn Chuter, lifestyle medicine practitioner and naturopath.

This article was co-written by Rebekah Barnett and Robyn Chuter to accompany the Inform Me webinar on measles. Readers can find more of Robyn’s work on her Substack, EmpowerEd.

This article is intended for educational purposes only and should not be taken as medical advice. It is recommended to consult a healthcare or nutritional medicine professional to determine what interventions and care are right for you and your family.

Comments on this post are open for readers to share their experiences and resources.

INDEX

1. What is measles? Symptoms, risks, and any benefits?

2. Is it true that measles was eradicated in Australia in 2014?

3. What has been the measles incidence rate in recent decades, and what explains the recent uptick?

4. Is there data to show if the recent measles cases are among vaccinated or unvaccinated people?

5. What types of vaccines are administered to children and adults in Australia, and what are the associated benefits and risks?

6. Is it true that the vaccine prevents the spread of measles?

7. Can “herd immunity” be achieved by vaccination?

8. What other treatments for measles are available?

9. How to spot the signs of a measles infection so as to act in the best timeframe?

10. How to talk to doctors to get the best treatment if a case becomes serious?

11. What other kinds of health professionals can people turn to outside of the GP clinic and hospital settings?

12. Learning from mistakes: Following the recent measles-associated deaths of two unvaccinated children in Texas, what went wrong, and what can be learned?

13. Link to webinar

1. What is measles? Symptoms, risks, and any benefits?

Measles begins with symptoms that resemble any upper respiratory tract infection. According to the WHO, early symptoms usually last 4–7 days. They can include:

running nose

cough

red and watery eyes

high fever

fatigue and malaise (feeling tired and generally unwell)

2-3 days before the measles rash develops, small bluish-white spots known as Koplik’s spots appear in the inner lining of the cheeks and lips of around 60-70% of people suffering from measles.

The rash begins about 7–18 days after exposure, usually on the face and upper neck. It spreads over about 3 days, eventually to the hands and feet. It usually lasts 5–6 days before fading. The rash consists of flat, tiny spots and raised bumps that eventually join together.

Measles is extremely contagious. It’s estimated that an infected person will transmit the virus to 9 out of 10 contacts if they do not already have immunity (either via prior infection or successful vaccination).

Spread occurs via airborne droplets or contact with nose or throat secretions, as well as contaminated surfaces and objects. The measles virus can stay in the environment for up to 2 hours.

People with measles are considered infectious from 24 hours prior to the onset of initial symptoms until 4 days after the rash appears.

Therefore, learning to spot the early warning signs is imperative to make sure you stay home, rest, apply early treatment, and watch for warning signs should complications develop. However, since the symptoms are so nonspecific at first, measles almost invariably spreads before the person (or parents) realise that they should be isolating to prevent infecting others.

Risks of measles infection

The major potential complications of measles are:

Pneumonia, which occurs in 2–27% of children in community-based studies (the wide range suggesting that poverty, malnutrition, overcrowding, and other socioeconomic factors play a large role in susceptibility to pneumonia).

Encephalitis, including subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (progressive neurodegenerative disease caused by the persistence of measles infection).

Immune amnesia, whereby immunosuppression after a measles infection can increase susceptibility to other infectious diseases - mostly within a few weeks from infection, but even up to 2-3 years. However, it is important to note that the immune amnesia hypothesis is based on research conducted on non-human primates, and on mathematical modelling of historical data, and it is contradicted by a body of research conducted in human children, which found that there is no persistent T lymphocyte immunosuppression or increased mortality after measles infection [ref, ref, ref, ref].

Other risks identified by the WHO include blindness, severe diarrhoea, ear infections, and preterm birth in pregnancy.

And, the most severe potential complication, death. It is estimated that the fatality rate of measles is 0.1-0.2%.

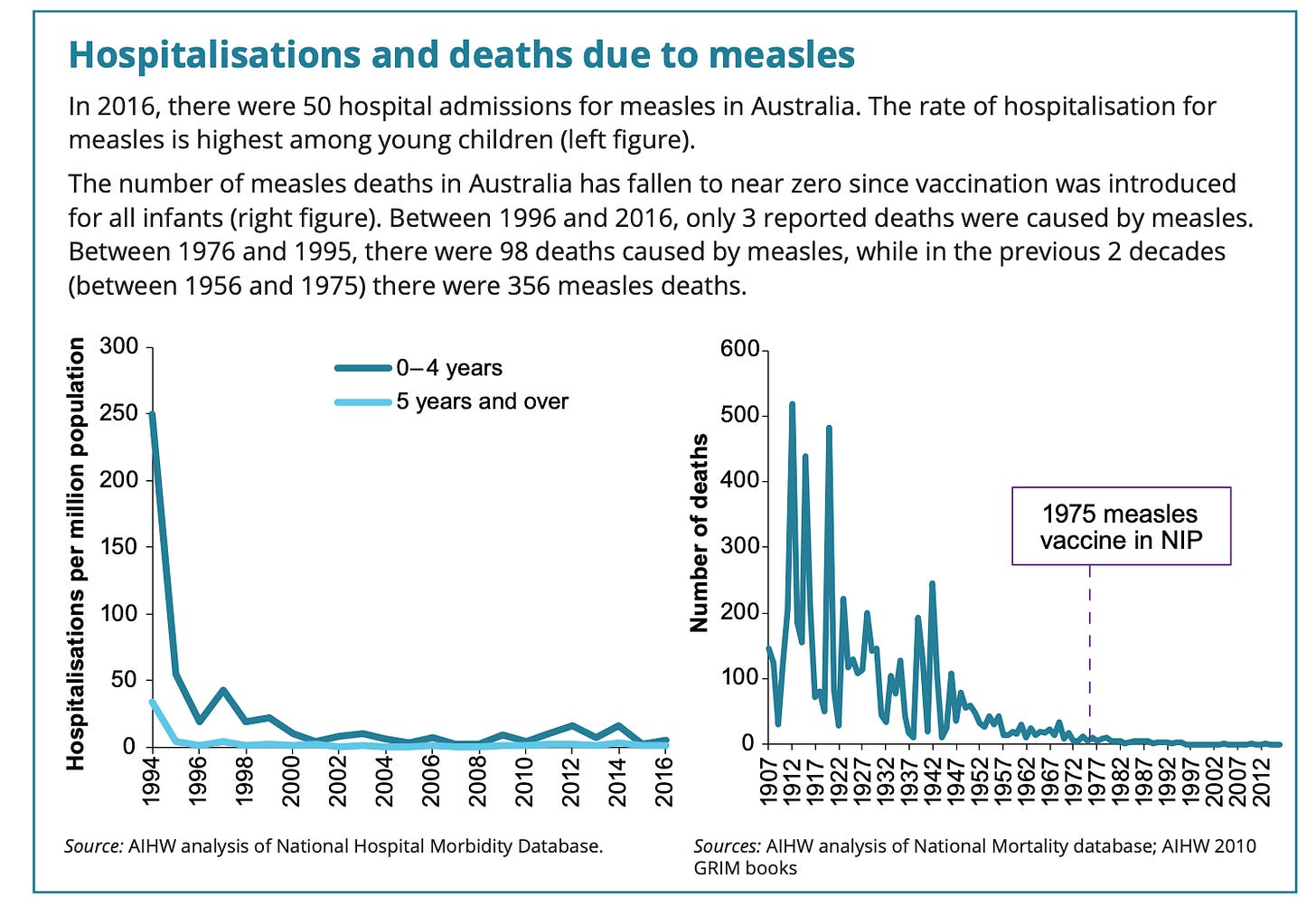

In Australia, there have been 3 measles deaths recorded in the past 30 years, according to data from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Prior to that, Australia counted 98 measles deaths in the 20 years 1976-1995, and 356 measles deaths in the 20 years 1956-1975. The AIHW attributes this decline in measles deaths to the introduction of routine childhood vaccination.

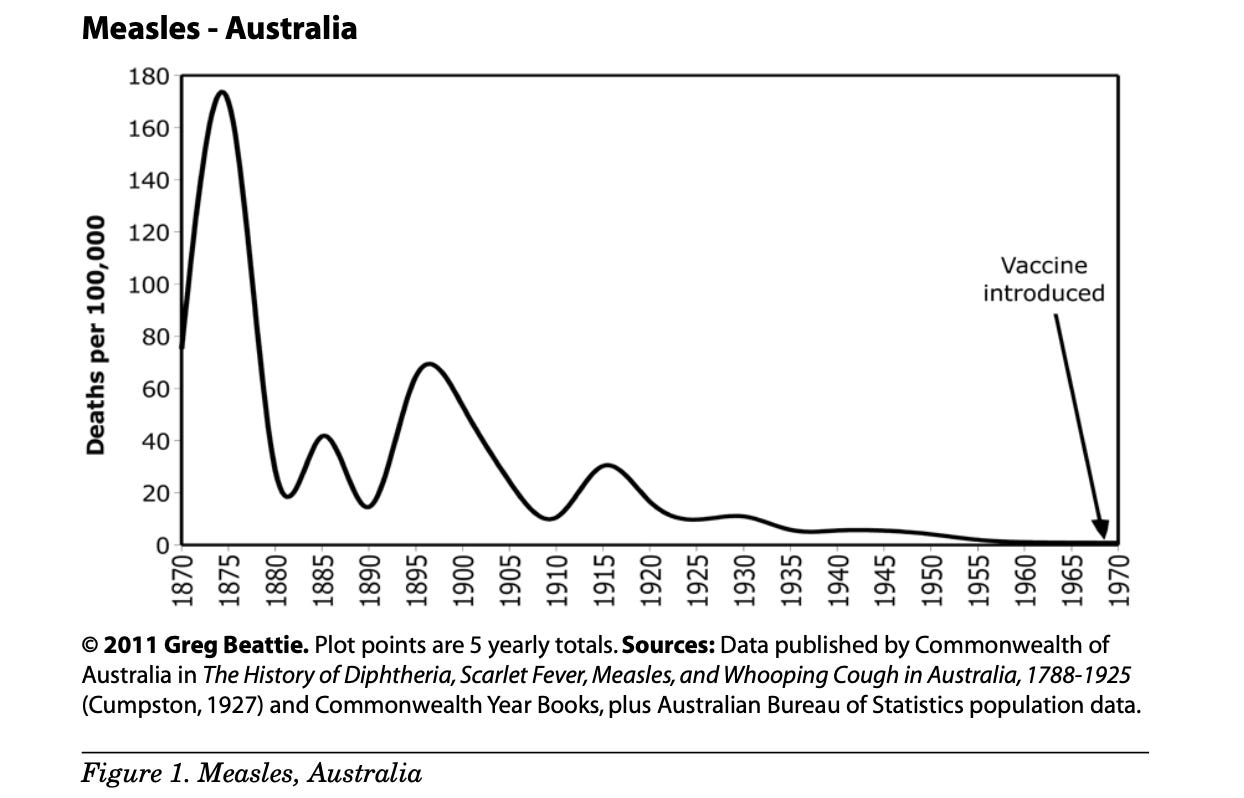

Another way of looking at the data, however, is as below. Clearly, while the introduction of the childhood vaccine is associated with a decline in measles fatalities, other factors (such as sanitation, access to antibiotics, and better primary health care systems) have played an arguably far more significant role in dramatically reducing the risk of death from measles.

This 1977 study by McKinley and McKinley estimates the contribution of vaccinations and other medical measures to the decline in measles mortality to be relatively “minute,” after the death rate had already dropped significantly due to other factors, a hypothesis borne out in the graph above.

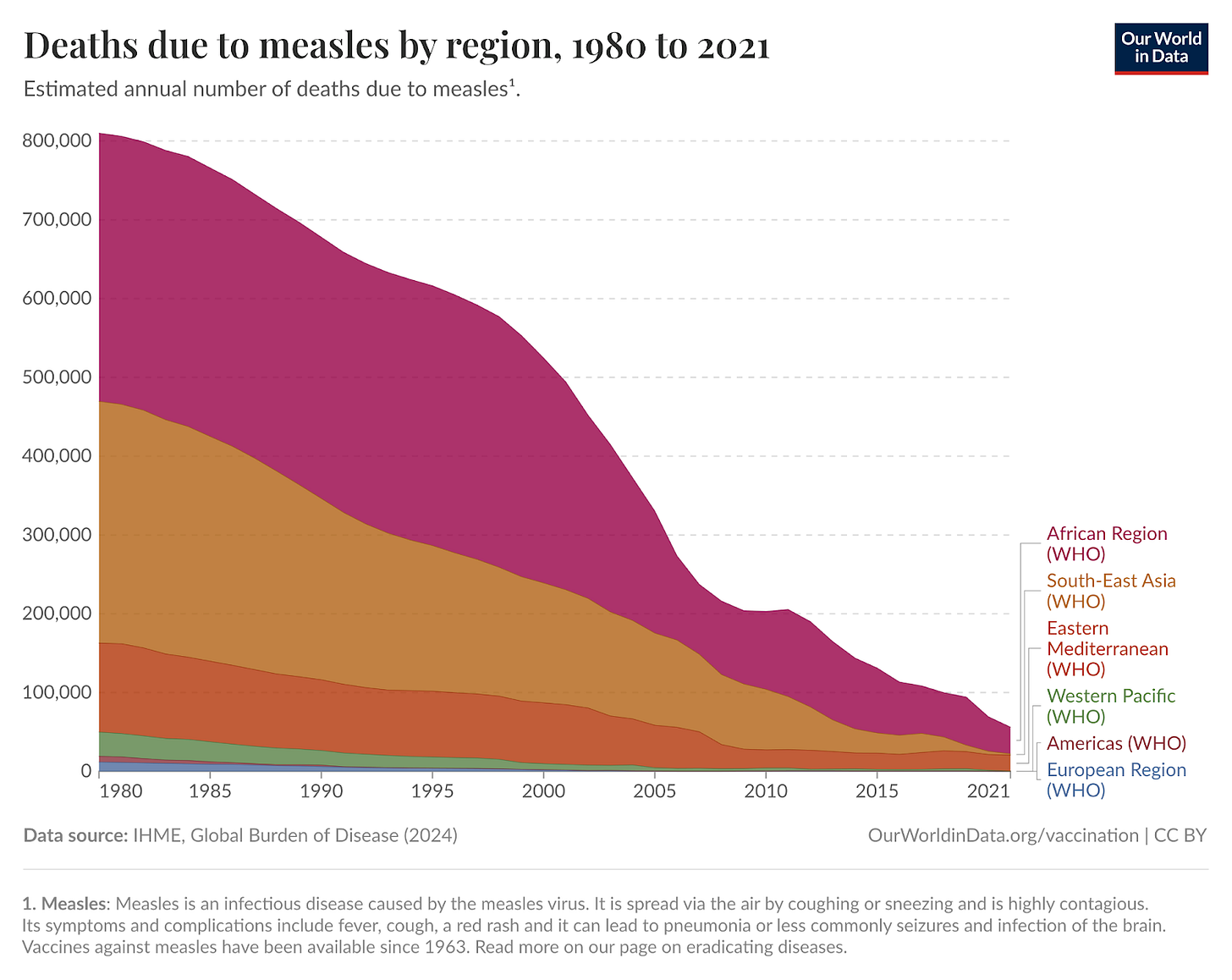

In terms of deaths globally, there has been a marked decline over the past 4 decades, from approximately 810,000 deaths in 1980 to 56,000 deaths in 2021. The majority of deaths are in the African Region. This decline is likely due to a combination of better sanitation and primary healthcare, as well as increased vaccination.

Benefits afforded by recovering from a measles infection:

Lifelong immunity, whereas vaccine-induced immunity wanes in 2-10% of vaccinees, leaving them susceptible to infection at older ages, when complications are more likely.

Broader immunity that protects against a greater number of wild-type measles strains; one study found that naturally immune individuals could resist 18 out of 20 measles strains, while vaccinated individuals were only protected against 10 out of 20.

Greater ability of mothers to protect their infants from measles, via transfer of maternal antibodies. Naturally immune mothers pass on more antibodies than vaccinated mothers, and these maternal antibodies are able to protect their babies for up to 10 months, whereas antibodies from vaccinated mothers wane by 3 months.

Association with decreased risk of developing allergic and atopic disease, Parkinson’s disease, and of developing or dying from several types of cancer.

2. Is it true that measles was eradicated in Australia in 2014? Is there a difference between eradication and elimination?

No, measles was not eradicated in Australia, but it was declared “eliminated” by the WHO in 2014, meaning that endemic transmission was sufficiently interrupted for a period of at least 36 months to meet the WHO’s criteria. ‘Eradication,’ on the other hand, means that the disease no longer exists - like smallpox.

Ironically, Australian media reported a “surge” in the number of measles cases for that same year, with 340 cases nationwide in 2014, 62 of those being in children under the age of 5, prompting calls for increased uptake of vaccination much like we are seeing now. Cases were thought to have arisen predominantly from incoming travellers.

It is highly unlikely that measles will ever be completely eradicated due to its extremely high transmissibility - especially during the early phase when it’s not obvious that the symptoms are due to measles rather than to a ‘standard’ upper respiratory tract infection - and the fact that the vaccine is subject to both primary and secondary failure (see section #6).

3. What has been the measles incidence rate in recent decades, and what explains the recent uptick in Australia and in other places around the world?

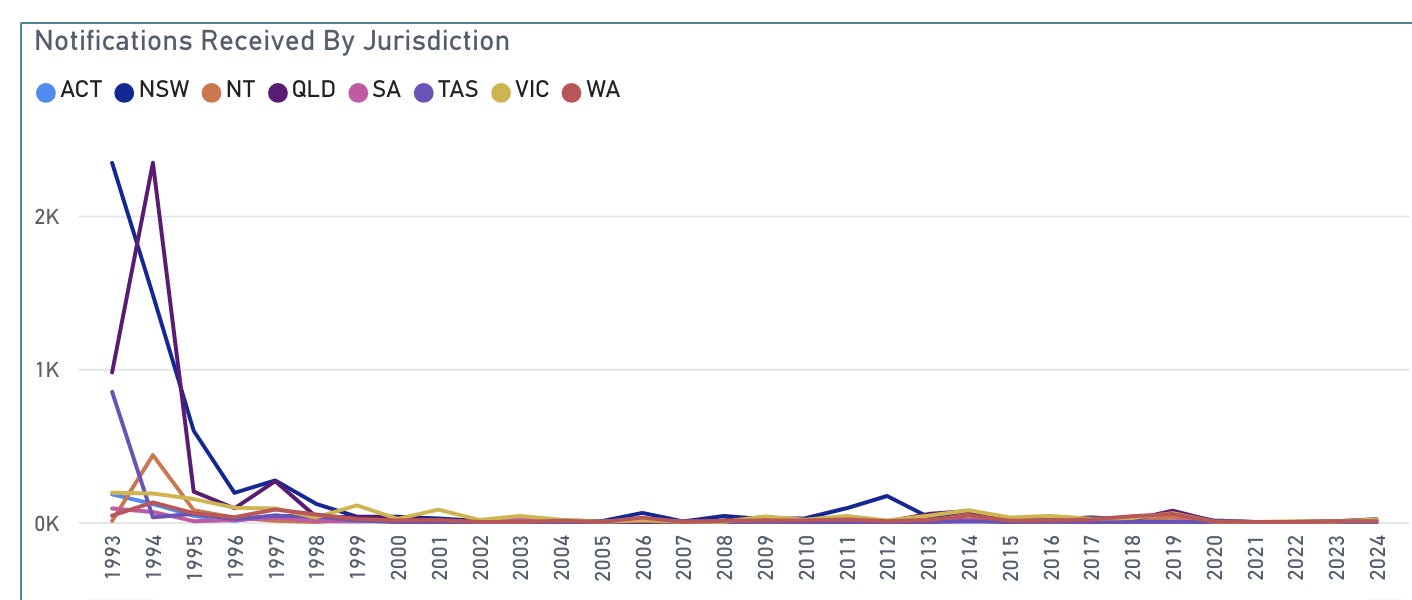

Measles cases in Australia have remained consistently low for decades, hovering between zero to a few hundred in any given year. The last major outbreak of measles occurred over 30 years ago, in the early 1990s, when Australia recorded up to almost 5,000 cases per year.

During 2020, 2021, and 2022, when Australia’s federal and state borders were closed for much of the time and the country lurched from lockdown to lockdown, cases dropped to 25, 0, and 7, respectively.

This year, Australia has recorded 63 measles cases as at 24 April, appearing to be returning to its pre-pandemic range of up to a few hundred cases per year.

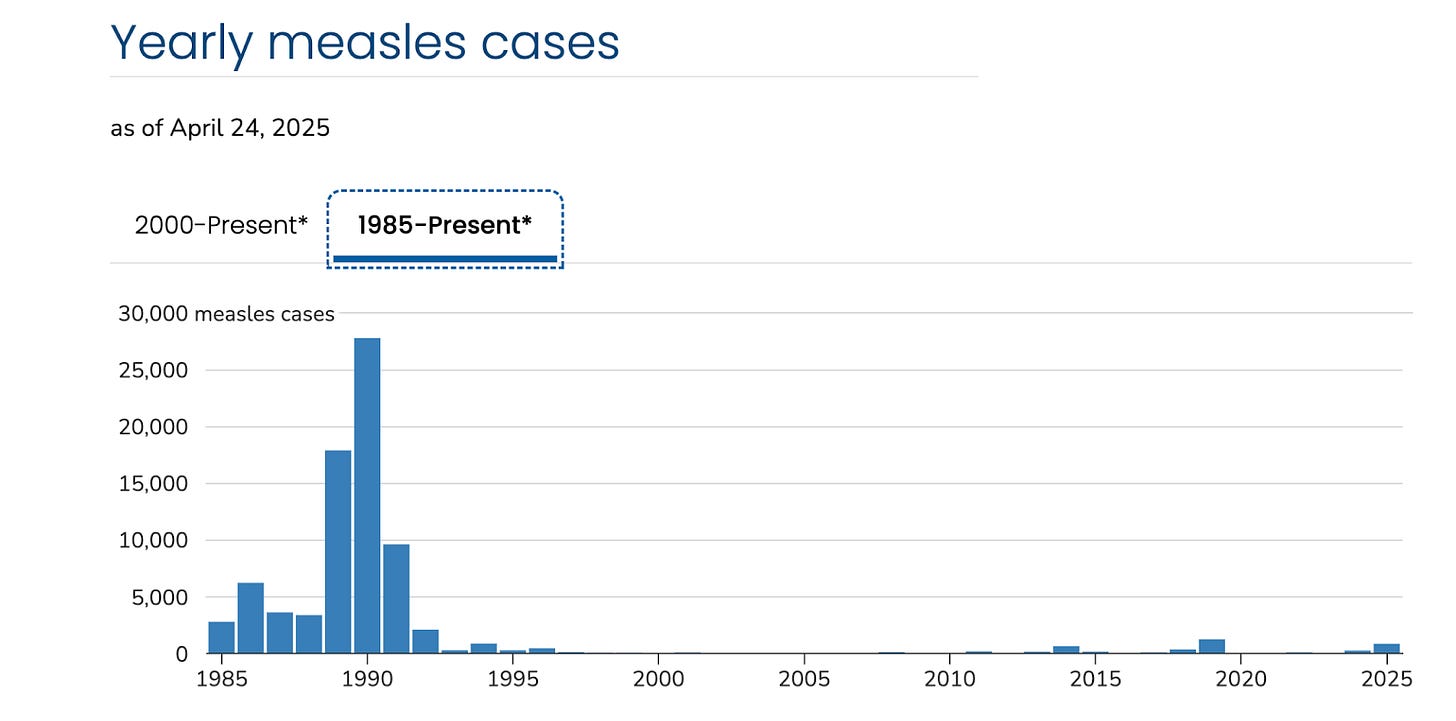

In the US, CDC data show that 2025 is a surge year for measles cases, after a lull throughout the pandemic years. 2019 and 2014 were also surge years. Similar to Australia, the 1990s (and mid-late 80s) saw much higher rates of measles case reports than present day.

4. Is there data to show if the recent measles cases are among vaccinated or unvaccinated people?

No. Media reports blame lowering vaccination rates for the spread of measles, but there are no publicly available data to show whether cases are occurring (and spreading) in vaccinated or unvaccinated individuals.

5. What types of vaccines are administered to children and adults in Australia, and what are the associated benefits and risks?

A stand-alone measles vaccine is not available in Australia; only MMR (measles-mumps-rubella) and MMRV (MMR + varicella/chickenpox), as listed in the Australian Immunisation Handbook (AIH). There are 2 versions of each, made by Merck and GSK. They are administered as follows:

Priorix-Tetra® (GSK) or ProQuad® (Merck) - 18 months

All are live attenuated vaccines, meaning that they contain ‘live’ virus that has been weakened so that it is not able to cause infection (in theory!). These vaccines are produced in chick embryo cell culture, and contain gelatin from pork, bovine serum albumin (protein derived from calves’ blood), and components of human cells, including aborted fetal tissue (MRC-5 and WI-38 cells).

It is recommended that children receive two doses, one of MMR at 12 months of age, and one of MMRV at 18 months of age. Adults who have not previously received 2 doses of vaccination are recommended to undergo serological testing and, if no immunity to measles is detected, to receive 2 doses of vaccination.

Benefits

The primary benefit of the combination measles vaccines is a greatly reduced (but not eliminated) risk of contracting measles, and therefore reduced risk of associated complications.

In cases where a vaccinated person contracts measles, evidence suggests that most cases are milder with lower risk of severe complications.

Measles vaccination may also reduce overall childhood mortality, particularly in low-income countries. Like viruses, vaccines can have ‘non specific effects’ (NSE) whereby overall childhood mortality is increased or decreased in vaccinated populations, in addition to a vaccine’s effect on the targeted disease. While the DTP vaccine is associated with negative NSE, measles vaccination has been associated with beneficial NSE.

Risks

Because these are live attenuated vaccines, all can revert to virulence, meaning that they can, in rare cases, cause all the symptoms of measles including pneumonia, aseptic meningitis, encephalitis/encephalopathy, and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (a rare and potentially fatal brain disorder). Measles vaccine shedding has been detected up to 29 days post-MMR vaccination. Immunosuppressed people are generally advised to avoid contact with anyone recently vaccinated with a live virus vaccine for this reason.

There is a lengthy list of other associated adverse effects on the product information sheet for each vaccine (linked above), which you can obtain from the manufacturers’ or TGA website. For example, the product information sheet for Merck’s M-M-R® II lists high fever, febrile convulsions, anaphylaxis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, ataxia, transverse myelitis, and optic neuritis, among many other adverse effects, and no data are available for effects on fertility.

There are 10 reported deaths to the Australian DAEN (like the US VAERS or UK Yellowcard systems) following vaccination with the above 4 mentioned vaccines since their introduction; however, the TGA emphasises that these may or may not be causally linked to vaccination.

The incidence rate of injuries and deaths associated with measles vaccines is hard to quantify for three main reasons.

First, vaccines are rarely, if ever, safety tested in long-term trials against an inert placebo. Rather, they are tested in short-term trials against other vaccines, so the safety data is very limited in that it can only tell you the safety profile of one vaccine compared to another, and only for a short period. We know from documents obtained by the Informed Consent Action Network (ICAN) that the trials for M-M-R® II or Priorix® did not use an inert placebo, and only collected safety data for 42 days - 6 months.

Second, it is well-established that passive surveillance systems like the DAEN underrepresent total injuries and deaths experienced within a population in relation to medicines by 10-100 fold - this is called the Under Reporting Factor (URF) [ref, ref, ref].

Third, pharmaceutical companies employ any number of tactics to produce favourable trial results, including the appearance of minimal adverse effects. The book Bad Pharma by Ben Goldacre gives a good overview of the kind of foul play that is routinely used in the pharma industry. OpenVAET on Substack has extensively documented alleged fraud and misrepresentations of the Pfizer Covid vaccine RCT data, as another example.

6. Is it true that the vaccine prevents the spread of measles?

Yes, mostly. According to a review of the scientific literature on measles published in the MDPI journal Microorganisms in 2022, secondary vaccine failure (where the vaccinated person contracts a measles infection due to waning immunity) is believed to occur in 2-10% of cases, most commonly between 6-26 years from the last vaccine dose. However, such breakthrough cases are generally associated with lower viral loads and milder disease. Primary vaccine failure (where the vaccine does not induce antibodies, leaving the vaccinee susceptible to infection) occurs in approximately 5% of vaccinees.

Since measles can only be spread by an infected person, to the degree that the measles vaccine actually works (i.e., does not incur primary or secondary failure), then it prevents the spread. However, if a vaccinee does contract measles, they are still able to transmit it to others.

7. Can “herd immunity” be achieved by vaccination?

Received wisdom says that 95% of the population must receive two doses of measles vaccination in order to achieve herd immunity, which the AIH defines as “A situation in which a large proportion of the population is immune to a disease through previous vaccination or illness. As a result, it is highly unlikely that the disease will spread from person to person,” and, “Non-immune people are indirectly protected from the disease.”

In Australia, vaccination rates fall a few percentage points shy of this herd immunity goal: In 2024, 92% of 2-year-old children had received two MMR vaccinations. This is in keeping with Australian childhood vaccination trends in general, which have been in gentle decline (by 1-2 percentage points) since 2021, which times with the Covid vaccination rollout. Other countries, such as the US, are also reporting a small dip in childhood vaccination rates for the same time period.

Thresholds for vaccine-derived herd immunity have changed over time, and the goal of eradication remains elusive.

When the goal of eradicating measles through vaccination was set in the late 1960s, it was assumed that “considerably less than 100 percent” of children would have to be vaccinated, based on A. W. Hedrich’s observations that once 55% of non-immune children had contracted measles, community transmission was suppressed for several years until the pool of susceptible children built up once again. The designers of the eradication strategy confidently declared that “the course of measles that will follow a nationwide control program will be comparable to that of smallpox; namely, the total disappearance of the infection promptly when the immunity thresholds have been attained.”

As this prediction was not achieved by the late 1970s, the target immunity threshold was raised to 90-95%. However, multiple measles outbreaks have occurred in schools in which over 95% of children have been vaccinated, including schools with a documented 99%+ vaccination rate.

8. What other treatments for measles are available? Before the vaccine, how was measles treated?

Before the measles vaccine, the condition was managed with good supportive care - rest, hydration, and nutrition - and antibiotics in cases of pneumonia.

Vitamin A is currently recommended by the World Health Organisation (WHO) for all children with acute measles regardless of their country of residence, and should definitely be given to all children with severe measles (i.e., requiring hospitalisation). Vitamin A should be given once daily for 2 days, at the following doses:

200,000 IU for children 12 months or older;

100,000 IU for infants 6 through 11 months old; and

50,000 IU for infants younger than 6 months.

An additional (i.e., a third) age-specific dose should be given 2 through 4 weeks later to children with clinical signs and symptoms of vitamin A deficiency.

According to Cochrane, the internationally-recognised peak body for establishing the evidence base of medicine, vitamin A supplementation is associated with a clinically meaningful reduction in measles-related morbidity (sickness) and mortality (death) in children.

While there is no literature on supplementation with vitamins C and D for reducing the severity and potential of complications from measles specifically, these vitamins are typically recommended for immune support in general [Vitamin C ref, ref, ref; Vitamin D ref ref ref, ref].

Ideally, for children at high risk, a blood test would be advisable to check levels of vitamins C and D. Professor Ian Brighthope recommends that ideal vitamin D levels should fall between 100-150 nanomoles per litre. Note that vitamin D levels fall in response to infection, as the body converts the storage form of vitamin D - which is what’s measured in the blood test - into the active hormone form which helps the immune system to fight off bacteria and viruses.

It is generally agreed that the appropriate range of vitamin D supplementation for general maintenance is between 800-2,000 IU/day. High-dose regimens of vitamin D supplementation (50,000 IU/week or 10,000 IU/day) can be effective for rapid deficiency correction, especially in high-risk groups (e.g., elderly, hospitalised patients). Bolus doses (>100,000 IU) are believed to be less effective for immunity and risk toxicity.

Vitamin C powder in water or juice can be administered to children in amounts of ½ to 1 tsp once or twice a day (as determined by bowel tolerance). High doses of vitamin C (1–8 g/day orally, 10–20 g/day IV) can be considered in acute settings (e.g., sepsis, viral infection) to reduce oxidative stress and inflammation (evidence is promising but not definitive). This is considered safe for short-term use but requires monitoring for side effects (e.g., kidney stones in predisposed individuals).

Both vitamins A and D are available in cod liver oil, but it is important to note that the vitamin D content of cod liver oil is highly variable between manufacturers and vitamin D toxicity has occurred from use of a product that had 3 orders of magnitude higher levels of vitamin D than declared. Therefore, it is recommended to use separate supplements of vitamins A and D in order to minimise risk of inadvertent overdosage.

It is possible to ‘overdose’ on vitamins A, C, and D. Too much vitamin A can result in headaches, rash, stomach pain, and vomiting. Too much vitamin D can cause an excessive amount of calcium in the blood, which will in turn cause aches and pains (monitoring 25(OH)D levels (25-hydroxyvitamin D, also known as calcidiol) is critical to avoid toxicity). Too much Vit C will cause wind and loose bowels, and kidney stones.

It is recommended to consult a medical or healthcare professional qualified in nutritional medicine for advice on what supplementation is right for you and your children. (Search at this link for a practitioner in your area).

9. How to spot the signs of a measles infection so as to act in the best timeframe?

Look for the early warning signs:

running nose

cough

red and watery eyes

small white spots inside the cheeks [these are not strictly speaking warning signs, as they appear after several days of nonspecific symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection]

Of all of these, the little white/bluish spots will be the best way to spot whether the virus is measles as opposed to any other cold/flu-like disease.

Understanding correct management of fever is essential to nipping symptoms in the bud as much as possible, and reducing risk of complications. The key elements of rational fever management are:

Avoid the use of medications that suppress fever (paracetamol/acetaminophen and ibuprofen), as these hamstring the immune response to infection, increase viral load and viral shedding, prolong the illness, increase the risk of complications, and do not prevent febrile seizures. Instead, provide thermal support by keeping the child warm enough during the first stage of the fever to prevent shivering, and then uncovering them to help them cool down through sweating once the fever breaks, but drying them off so they don’t become clammy.

Provide enough fluids to prevent dehydration, but do not overhydrate as pushing fluids into the body at this time increases the risk of hyponatraemia (low blood sodium levels), which is associated with worse outcomes of infection, and the pooling of fluid in the lungs, which impairs breathing and increases the risk of pneumonia. In general, thirst should determine the amount of liquids consumed, but parents should watch for signs of dehydration, listed here.

Reduce or eliminate food intake; children usually lose their appetite when sick anyway, so respect this and don’t try to tempt them to eat until they’re hungry again.

You can learn more about rational fever management here and here.

10. How to talk to doctors to get the best treatment if a case becomes serious?

Get informed about measles and its complications before you or your child gets sick! In general, you’ll receive better treatment if you:

a) Demonstrate that you know what you’re talking about, by using relevant medical terminology such as Koplik’s spots, fever (rather than ‘high temperature’), and sputum culture;

b) In cases where a child is not vaccinated, avoid medical discrimination/bias (even subconscious) by deflecting questions about your child’s vaccination status with statements to the effect that your child has had all the vaccines s/he needs;

c) Politely but firmly request evidence-based diagnosis (e.g., sputum culture with susceptibility testing) and treatment (e.g., antibiotics selected on the basis of susceptibility testing).

It is recommended to purchase vitamins A, C, and D from a health food store or pharmacy and administer them to your child, as this is highly unlikely to be part of hospital protocol, despite the WHO’s endorsement of vitamin A supplementation for all children with measles.

11. What other kinds of health professionals can people turn to outside of the GP clinic and hospital settings?

Integrative medical practitioners and non-medical health practitioners, including naturopaths and herbalists, can complement allopathic medicine, and it is advisable to build a relationship with a professional (or several) with some kind of integrative/functional/holistic experience before crisis hits.

12. Learning from mistakes: Following the recent measles-associated deaths of two unvaccinated children in Texas, what went wrong, and what can be learned?

A review of the medical records of both children by Dr Pierre Kory suggests that the primary problem was the administration of incorrect antibiotics for differing types of pneumonia.

In one case, the pneumonia appears to have been a secondary complication of measles.

In the other, the pneumonia was acquired in the hospital when the child was initially brought in after a bout of serial illnesses, of which measles appeared somewhere in the mix several weeks in.

The fact that both of these unfortunate events have been used to drive hysterical reporting about “measles deaths” suggests that deaths may in fact be overestimated - only one of these deaths could reasonably be attributed to a chain of events arising from measles infection. Additionally, both of these deaths appear to have been avoidable.

The most important thing that was missed in both cases was timely testing of the sputum culture to determine what type of pneumonia the girls had, which was needed to inform which antibiotics they should be given. Tragically, both children were given antibiotics that did not treat the types of pneumonia that they had - which likely would have saved their lives.

Patients or carers of children suffering from pneumonia can request a sputum culture with susceptibility testing (MC&S swab for short) on admission to ensure that this does not happen to you or your family. The culture should be repeated if the antibiotic does not appear to be working, or if the patient initially improves but then relapses, as new microbial agents (including hospital-acquired infections) can complicate the pneumonia.

13. Link to webinar

Watch Measles, a Balanced Perspective for a more in-depth discussion of the issues, including extra questions from the live audience.

This webinar was produced by Inform Me, a series of podcasts and online resources dedicated to unpacking the Australian Childhood Immunisation Schedule.

By offering a judgment-free zone filled with comprehensive information, expert insights, and real-life stories, Inform Me aims to bridge the gap between traditional wisdom and modern research. It’s not just about providing facts; it’s about creating a community where parents can explore their concerns, find compassionate support, and ultimately make informed decisions that align with their family’s unique needs and values.

About the authors

This article was co-written by independent journalist Rebekah Barnett, and lifestyle medicine practitioner and naturopath Robyn Chuter.

About the panellists

Dr Joe Kosterich

GP, speaker, author, media presenter, and health industry consultant. Dr Joe is WA State Medical Director for IPN, Clinical Editor of Medical Forum Magazine, Medical Advisor to Medicinal Cannabis company Little Green Pharma and Vice Chairman of the Arthritis and Osteoporosis Association of WA. Dr Joe has self-published two books: Dr Joe’s DIY Health and 60 Minutes To Better Health, and maintains a website with health information and commentary. He is often called to give opinions in medico-legal cases, has taught students at UWA and Curtin Medical schools, and has been involved in post-graduate education for over 20 years.

Prof Ian Brighthope

With Bachelor’s degrees in Medicine and Surgery, Professor Brighthope went on to become founding president of the Australasian College of Nutritional and Environmental Medicine (ACNEM), where he remained president for over 26 years and pioneered the first post-graduate medical course in nutrition and its related fellowship in Australia. In 2017, Prof Brighthope initiated the establishment and content of Australia’s first RACGP Category 1 CPD points course in medicinal cannabis, and he is an official ambassador to the peak body Complementary Medicines Australia (CMA). Prof Brighthope regularly travels in Australasia delivering lectures on best health principles in medical practice. His lifelong ambition is to help change the way medicine and healthcare are practiced for the benefit of the public and to see nutrition, nutritional and environmental medicine, and herbal medicine become the building blocks and keystones to world health and peace.

Robyn Chuter is a highly experienced health practitioner with a Bachelor of Health Science from the University of New England, a Bachelor of Health Science with First Class Honours from Edith Cowan University, and a Diploma of Naturopathy from the Australasian College of Natural Therapies. Robyn is also an Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine-Certified Lifestyle Medicine Practitioner, and is proud to be a Fellow of the Australasian Society of Lifestyle Medicine. She publishes on her Substack, EmpowerEd.

To support my work, share, subscribe, and/or make a one-off contribution to my Kofi account. Thanks!

Mid boomer here with siblings who caught the whole box and dice, back in the days when Mums worked solely at at home. The Mums knew the drill and the older ones counselled (and consoled!) the young new Mums, reassuring and advising. We had daily dose of C.L.O (cod liver oil) and had to play ouside the house (Vit D). When an illness hit we were put to bed with extra blankets to keep the temperature up, regular fluids included egg-flips (eggs whisked up with milk, cream and vanilla) and chicken soup. Definitely NO sweets and NO sugar — the old women in the family were adamant that sugar ruined the immune response. Nourishment was given ONLY when awake - we slept uniterrupted - which was considered v important. With those of us under 10yo Mum had us sick with the childhood diseases at one time or another. We got sick, then got better. Job well done from my Mum who managed all her ten kids by herself. Lots if big families then - the lady up the road had fifteen. No one ever needed hospital for any childhood illness — the Mums' grapevine would've been all over that. No one in our 15K town died either (not one kid - over the 47 years Mum & Dad lived there) We all played something — netball, tennis or footy, and anything like death or bad news in a town that small, spreads like wildfire. Whoopteedoo..... kids get sick, recover, immune system more robust. We had GOOD nutrition! Free ranged our own chooks and grew our own vegies with no herbicides. Plenty of walking, playing in fresh air and sunshine. Lots of physical activities, like endless skipping throughout the year - except hot days. Could it be we were actually stronger back then? Are children being treated too preciously now, making them inadvertently fragile?

Trick is to focus on raising kids in a robust way - lots of outdoor activities in the sunshine, with awareness to avoid sunburn. Good quality nutrition, no crap food or "treats". We will never vaccinate death away. Our reliability on pharma is now beyond absurd.

Homeopathy is an effective form of treatment.